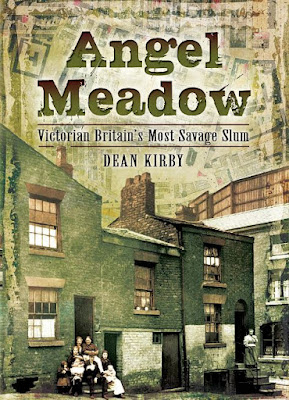

Dean Kirby Angel Meadow

Kirby, during research into his ancestry, discovered that his family had lived in Angel Meadow after moving from Country Mayo in the mid 1860's. In 2012, Kirby accompanied archaeologists who were excavating the area in search of evidence of the slum. His book reveals the information found on the slum life in 19th century Manchester. It was important in analysing Gaskell's representation of this life to compare it to historical fact.

Wider context to Gaskell’s depiction of slum and

working communities.

Dean Kirby, Angel Meadow Victorian Britain’s Most

Savage Slum, (Great Britain: Pen & Sword History, 2016)

Within Gaskell’s work she notes that Esther, Mary’s

aunt, lives in Angel Meadow, a notorious slum that thrived in early industrial

Manchester. Kirby wrote the book after tracing back his ancestors who had lived

in the slums.

Chapter 2 The Meadow pp. 12 – 18.

‘Smoke from the engines billowed into the houses and

stained the walls and ceilings with soot… The rivers began to run murky and

thick with pollution. Tall chimneys rose up around the train, the grass turned

brown, the trees grew stunted and the paths were blackened with coal dust.’

Victorian passenger Edwin Waugh ‘moral desert,

swarming hive of ignorance, toil and squalor.’ 1855.

‘Until the late eighteenth century, anyone standing at

the top of Angel Meadow would have gazed down upon fields tree-lined lanes and

the dusky coloured River Irk, which teemed with trout and eels.’

Essayist Benjamin Redfern ‘lamented the loss of this

heavenly landscape, which he said had been one of the most beautiful views of

vale and river, hill and woodland.’

‘Angel Meadows first residents included professionals

and tradesmen: flour dealers, bakers, shuttle-makers, hatters and dress

designers… Cows still grazed in the few remaining undeveloped fields and milk

was sold from nearby dairies or ‘milk houses. But even in those halcyon days,

Angel Meadow was earning a dubious reputation.’

‘It was

unsurprising that thieves were drawn like moths to Angel Meadow, when the

area’s inhabitants had every luxury and amenity. Towards the end of the

eighteenth century, the local residents even had their own pleasure ground.’

‘In the last

quarter of the eighteenth century, Angel Meadow seemed to provide its wealthy

residents with every comfort, but its popularity faded overnight. As Manchester

grew, the areas closest to the town centre became dominated by industry. The

merchants and artisans fled to the new areas, such as Ardwick Green to the

east, which was now within trotting distance of their carriages. Angel Meadow

quickly became a slum.’

‘Unscrupulous

landlords stopped carrying out repairs and their occupants began using the

houses’ wooden frames as firewood, leaving them in a permanent state of ruin.

Covered passages soon led from the streets to inner courts where no two human

beings could pass at the same time.’

‘Engels found that

cottages were built by the dozen, with walls the width of just half a brick. He

wrote: ‘Of the irregular cramming together if dwellings in ways which defy all

rational plan, of the tangle in which they are crowded literally one upon the

other, it is impossible to convey an idea.’

Chapter 5 The

Cholera Riot pp. 32 – 39. – context to the illness the Davenport’s have.

‘Cholera arrived

in Manchester in May 1832.’ Disease known as the blue death – turned victims

skins blue-grey, came ashore in Sunderland when a ship of sailors docked in the

port and spread through London, Glasgow and Belfast before it reached

Manchester.

It reached the

city through the railway to Liverpool which had opened in 1830. Due to Angel

Meadow’s lanes lack of pavement the courtyards became dumping grounds for offal

and animal dung. Engels noted that ‘People remembered the unwholesome dwellings

of the poor and trembled before the certainty that each of these slums would

become a centre for the plague.’

Panic spread

through Manchester, a gardener named Alexander Whirk was murdered by his wife

as she feared after a week if diarrhoea he had caught the plague. 19 inmates

died at the New Bailey prison and six men died in one room in a workhouse.

Chapter 7 Hell on

Earth.

Dr. Gaulter wrote

of a court in Manchester. ‘You descend through a passage to the row of houses

on the river’s edge by interrupted flights of steep steps and you find yourself

at the bottom in a kind of well or pit, suffocated for want of air and half

poisoned by the effluvia arising from two conveniences which stand in the

centre of the well-like area.’ 18 people contracted the disease there in 48

hours.

‘Fever,

bronchitis, tuberculosis and typhus were the biggest killers in Angel Meadow

throughout the 1840’s. The slum had become a giant fever nest, with more than

900 cases recorded in one year alone. The worst outbreaks were in winter, when

people bolted their doors and stayed huddled around fires in the airless,

overcrowded rooms.’

The Manchester

Courier blamed the ‘unclean people’ drifting into Manchester in search of

work, who would have no access to bathing facilities when they arrived. Doctors

believed at the time that fever was caused by human waste, overcrowding, and

intemperance, and that typhus was incubated in the slum’s cesspools.

Old maps show how

conditions had deteriorated in the years since the outbreak. Victoria Station

opened below the workhouse in 1844 and the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway

viaduct soon curved over Angel Meadow and New Town.

The district’s

medical officer Dr Edward Meacham wrote to Whitehall urging government

ministers to intervene. His wish was granted and an inspector visited the

cemetery with the Earl of Shaftesbury who was attending a social science congress

in Manchester. The ground in Angel Meadow was eventually paved over.

Chapter 8

Family Life pp.56 – 62.

A stable family

life was rare in Angel Meadow, where troops of boys and girls became parents of

rickety children before they were out of their teens.

Dr James Phillips

Kay – investigated Angel Meadow, ‘Home has no other relation to him than that

of shelter – few pleasures are there – it chiefly presents to him a scene of

physical exhaustion, from which he is glad to escape.’

No back yards,

built back to back.

Chapter 10 – Lodgings

pp.71 – 78.

Angel Meadow was

the main lodging house district for the men and women pouring into Manchester.

1866 – 88 common

lodging houses, offering 2,653 beds ranging from 3 pence to a shilling a night.

As a result of this, Angel Meadow had a changing population of 3,724 lodgers on

top of its population.

Lodging housing

inmates were a mixture of vagabonds, wayfarers, workmen and harvestmen who

arrived and departed like swallows. A few had regular jobs but too low wages to

rent a house, others were educated men who had fallen on hard times.

Journalist from Manchester

Evening News, recorded that ‘more than 30 lodgers were sleeping in a long,

wide attic with boxed-off sleeping compartments running down either side. Rough

doors were fitted to the compartments for privacy, but they had no hinges and

had to be lifted out and dragged away before the occupants could get inside. The

owner had smashed through a partition wall into the attic of the next house to

create another dormitory… As the glare of the candle fell upon the sleepers’

eyes, some stared stupidly about, while others blinked and yawned as if too

overcome with sleep to care much about what was going on. As long as the light

remained, a babble of oaths and invectives could be heard.’

Biggest lodging

house in Manchester was called The Rest. Located in an old mill in Factory Yard

off Charter Street, contained beds for 600 lodgers. ‘Inside, they found a great

quadrangle with a concrete floor surrounded by wooden benches. A journalist for

the Manchester Courier, noted that ‘The lawyer and the merchant, having

flung him back on his wooden bench, walked away, not heeding the wound and he

still slept on in blissful ignorance of his injury. Nobody cared. Most of the

inmates went on playing dominoes, and all were completely indifferent. It was

sickening.’

Comments

Post a Comment